RIPA policy

In this section

Definitions

The essential key to understanding the way that RIPA works and how the council will use it, is to understand certain key definitions. Awareness as to whether a proposed action comes within RIPA is critical in establishing whether authorisation actually needs to be sought and at what level.

There are several categories of covert activity, some of which the council may potentially use. However on advice from inspecting Deputy Surveillance Commissioners and taking account of the nature and limited range of criminal offences which the council may investigate, this policy recognises that showing “necessity” and “proportionality” for some of these techniques in a council setting is unlikely and therefore the council is highly unlikely to use them. Additionally there are some activities which the council is prohibited by law from using.

| Type of activity | Brief description | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Directed surveillance | Covert surveillance which is not intrusive; undertaken for a specific operation in relation to a relevant offence and in a way likely to obtain private information about an individual | Council may use this |

| Covert Human Intelligence sources (CHIS) | This is the use or conduct of someone “undercover” that establishes or maintains a personal or other relationship with a surveillance subject for the covert purpose of obtaining information. | Council unlikely to use this |

| Communications data access | Access to data showing when particular communications took place, but not the content of those communications. | If required this will be through the National Anti-Fraud Network (NAFN) who are the Single Point of Contact for communications data. |

| Intrusive surveillance | Covert surveillance carried out in relation to anything taking place on any residential premises or any private vehicle where it involves a person on the premises or in the vehicle or is carried out by a surveillance device. | By law the council cannot use this |

Other key terms which can be usefully explained are:

| Term | Brief description |

|---|---|

| Surveillance | the monitoring, observing or listening to persons, their movements, their conversations or their other activities or communications or recording anything monitored, observed or listened to in the course of surveillance and includes surveillance by or with the assistance of equipment such as cameras, video recorder, binoculars or similar. |

| Private information | This term needs to be interpreted in line with the European Court for Human Rights explanation of private life and the latest code of practice. In essence it means private information includes any aspect of a person’s private or personal relationships with others such as family, professional and business relationships. |

| Non private information | May include information about a person which is in the public domain such as newspapers, journals, TV broadcasts, websites and articles. It may include information only available after the payment of a fee and any data which is made available on request. |

| Overt surveillance | To paraphrase the legal definition, this covers all situations where surveillance is not covert. It is done in the open, for example using uniformed staff, marked vehicles or public CCTV systems which scan a general area. Overt surveillance does not require authorisation under RIPA. |

| Covert surveillance | Means surveillance carried out in such a way calculated to ensure that the person who is the subject of the surveillance is unaware it is taking place, or surveillance carried out by use of a surveillance device. |

| Confidential information | Certain information relating to medical or religious counselling records, MP/constituent communications, legal privilege or journalistic sources. Only the councils Head of Paid Service (or appointed Deputy) may authorise surveillance to obtain confidential information. |

| Collateral intrusion | Information obtained during surveillance which relates to a third party who is not the subject of the surveillance. |

| IPCO | Investigatory Powers Commission's Office |

Council use of covert human intelligence sources (CHIS).

It is considered highly unlikely that the council will ever consider the deployment of CHIS as being necessary and proportionate, and to do so the Authorising Officer must be satisfied that the CHIS is necessary, that the conduct authorised is proportionate to what is sought to be achieved and that arrangements for the overall management and control of the undercover officer are in force. These can be onerous, and CHIS authorisations will not normally be granted owing to the threshold test of necessary and proportionality and the specific skills needed to operate, handle and manage CHIS.

However as pointed out during IPC inspections, it is important that council officers are aware of what constitutes a CHIS so that they do not inadvertently create one, therefore an explanation of CHIS and associated risks is included in the training for our investigatory officers.

Council use of communications data

As noted above, it is legally possible for councils to also undertake elementary communications interception but, it is unlikely that the Council will use this tool often.

If necessary, the Council will make this application through the National Anti-Fraud Network (NAFN) who is a single point of contact for communications data.

Council use of covert directed surveillance

Like all Local authorities in England & Wales the council can only authorise use of directed surveillance under RIPA to prevent or detect criminal offences that are either punishable, whether on summary conviction or indictment, by a maximum term of at least six months imprisonment or are related to the underage sale of alcohol and tobacco.

The council may therefore authorise the use of directed surveillance in more serious cases as long as they are satisfied that it is necessary and proportionate and prior approval of a Magistrate has been granted. Examples would include more serious criminal damage, serious waste dumping and serious or serial benefit fraud.

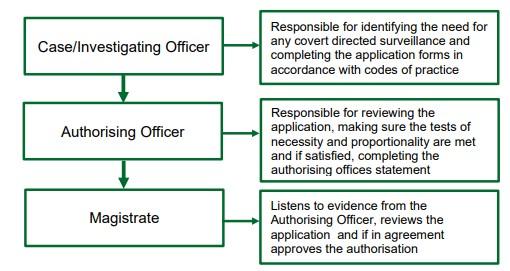

A local authority such as the Council MAY NOT AUTHORISE the use of directed surveillance under RIPA to investigate disorder that does not involve criminal offences or to investigate offences that are punishable, whether on summary conviction or indictment, by a maximum term of at least six months imprisonment. for example, littering, dog control and fly-posting. Three separate people are involved in granting an authorisation for covert directed surveillance by the council:

It is the responsibility of the investigating officer/case officer to determine if surveillance techniques may be appropriate to aid an investigation. They should have early discussions with a RIPA authorising officer to ascertain if RIPA authority is required (a suitable flow chart is included in appendix A)

Where a RIPA authority cannot lawfully be issued then the case officer is responsible for ensuring that only overt surveillance techniques are used and that no covert surveillance takes place.

It is council policy that covert surveillance will only take place with a lawful authority in place. If no RIPA authorisation can be given, and there is no other power to carry out the covert surveillance, then it must be made overt. Ways of making surveillance overt include:

- uniformed staff,

- notification of intentions,

- marked vehicles,

- signs

- publicity and

- ensuring the surveillance is not carried out in a way calculated to ensure the subject is unaware it is taking place.

In determining whether a RIPA authority is required and may be authorised the case officer will need to consider and be able to explain to the authorising officer:

- that the operation is in relation to a core investigatory activity

- whether the offence which is under investigation is one which is punishable by a maximum term of at least 6 months imprisonment or is a specified offence relating to the sale of alcohol or is a specified offence relating to the sale of tobacco

- that covert surveillance is necessary and proportionate to the matter under investigation

- that there are no alternative means of obtaining the evidence

- that a collateral intrusion risk assessment has been carried out

A RIPA authority can only be considered in regard to the prevention of crime relating to the above offences (or for disorder if it also meets one of the above definitions). Blanket authorisations covering “crime and disorder” are not allowed.

Once it has been decided that there is a need for covert surveillance or an undercover exercise, specific authorisation needs to be obtained. The case officer will need to complete the relevant parts of the authorisation form and one of the Council’s appropriately trained and authorised officers will need to consider the application and complete the authorising officers statement on the forms.

Applications for authorisations need to be framed in such a way that they do not require sanction from any person in the public authority other than the authorising officer (and magistrate).

Both the case officer and authorising officer must make sure they show why the surveillance is necessary and proportionate on the form. Sufficient detailed information must be provided, including for example the “who, what, when, where, why and hows” of the authorisation. It must be clear who has been authorised to do what, when they can carry it out and how they are to undertake the surveillance. Necessity and proportionality cannot merely be inferred from the gravity of the offence, and clear reasoning must be provided. The codes of practice provide further guidance as to necessity and proportionality and these terms are explored further in officer training.

When deciding whether or not authorisation is warranted in a particular circumstance the Authorising Officer has to ask four relevant questions:

- Is the surveillance for a relevant offence?

- Is the surveillance necessary for the purpose of preventing or detecting crime? In this context necessary means that there is no other way of obtaining the information other than by covert surveillance, i.e. all other investigatory tools and options have been exhausted or are wholly inappropriate

- Is the conduct of the surveillance proportionate to its aim? In this context proportionality requires consideration of

- Balancing the size and scope of the proposed activity against the gravity and extent of the perceived crime or offence

- Explaining how and why the methods to be adopted will cause the least possible intrusion on the subject and others

- Considering whether he activity is appropriate use of the legislation in a reasonable way having considered all reasonable alternatives of obtaining the necessary result

- Evidencing as far as reasonably practicable what other methods have been considered and why they were not implemented.

- What are the implications arising from a collateral intrusion risk assessment?

In simple terms can the objective of the surveillance be important enough to justify the interference with an individual’s liberty and privacy and the risks of obtaining information about third parties?

The Authorising Officer should also consider the means of surveillance and whether this is the most appropriate in the specific circumstances. Does it minimise intrusion into an individual’s private life and is it a workable method of obtaining information?

Authorising Officers should keep the scope of the authorisation to a minimum i.e. sufficient authorisation to gather the required information but nothing more. The Investigating Officer must be made fully aware of the limits of the authorisation.

There is an automatic three month restriction on the grant of any directed surveillance authorisation. Further authorisation will need to be sought for periods over this in the form of a renewal application. If a short sharp operation is envisaged then the correct procedure is to grant the authorisation for 3 months but to schedule an appropriate early review and to cancel the authorisation as soon as it is no longer necessary or proportionate.

In general authorisation should be sought punctually and in advance of the activity constituting the covert surveillance or use of CHIS. Wherever possible the circumstances of the case should be discussed with the authorising officer in order for a reasoned decision as to whether surveillance or CHIS is necessary and whether alternative means of obtaining information has been considered.

There is specific guidance in the code of practice regarding surveillance that may yield confidential information which includes:

- Matters subject to legal privilege as described in section 98 of the Police Act 1997.

- Personal information being information held in confidence concerning an individual (living or dead) who can be identified from it and who can be identified from it and relating to physical or mental health, spiritual counselling or other assistance or information which a person has acquired or created in the course of any trade, business, occupation or for the purposes of any paid or unpaid office.

- Confidential journalistic information which includes information acquired or created for the purposes of journalism and held subject to an undertaking to hold it in confidence.

It should be noted that changes to the legislation brought about by the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012 mean that an authorisation for surveillance can only be brought into effect once it has been approved by a JP/Magistrate.

Application for such approval must only take place once one of the council’s appointed authorising officers has signed off the application for surveillance as it will be the authorising officer who needs to provide evidence to the magistrate as to why the authorisation is needed.

The case officer and authorising officer will need to attend court having completed the necessary court application form and telephoned the court in advance to arrange a hearing. It is generally not good practice or appropriate to just turn up at the court house without prior agreement.

The JP/Magistrate will perform a paperwork review and this is why it is important that all relevant material is contained in the RIPA application. It will not be possible to introduce any additional evidence outside the content of the RIPA form.

The JP/Magistrate may grant the application, may choose to refuse it (in which case amendments can be made and a new application submitted) or may reject the application.

A RIPA application authorised by a local authority cannot take effect until judicial approval has been given. This may be different to other agencies who use RIPA so care must be taken when running joint operations.

The council’s legal team will arrange for access to a JP/Magistrate and in exceptional circumstances it may be possible to arrange this out of hours/outside of a court location.

Elected members, or members of council staff who are magistrates are obviously unable to authorise RIPA applications for council operations.